"As schol­ars of ancient texts well know, the recon­struc­tion of lost sources can be a mat­ter of some con­tro­ver­sy. In the ancient Hebrew and less ancient Chris­t­ian Bib­li­cal texts, for exam­ple, crit­ics find the rem­nants of many pre­vi­ous texts, seem­ing­ly stitched togeth­er by occa­sion­al­ly care­less edi­tors. Those source texts exist nowhere in any phys­i­cal form, com­plete or oth­er­wise. They must be inferred from the traces they have left behind-signatures of dic­tion and syn­tax, styl­is­tic and the­mat­ic pre­oc­cu­pa­tions...."

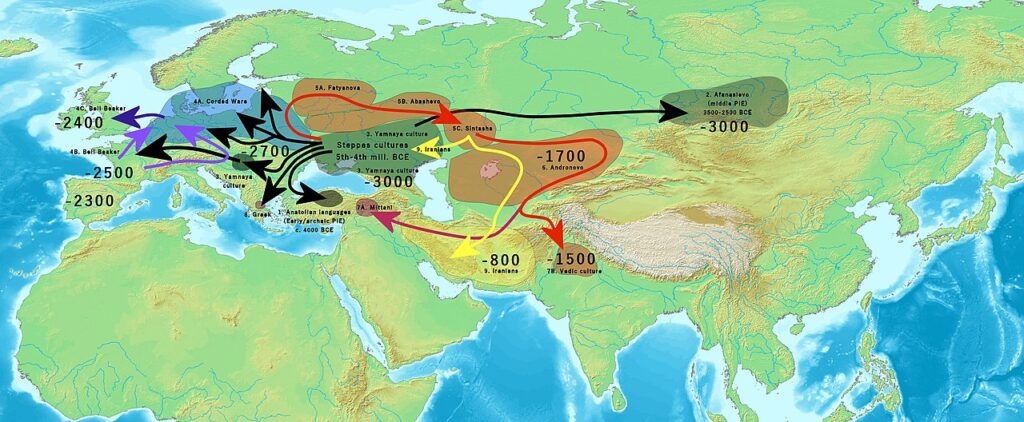

"So it is with the study of ancient lan­guages, but since oral cul­tures far pre­date writ­ten ones, the search for lin­guis­tic ances­tors can take us back to the very ori­gins of human cul­ture, to times unre­mem­bered and unrecord­ed by any­one, and only dim­ly glimpsed through scant archae­o­log­i­cal evi­dence and observ­able aur­al sim­i­lar­i­ties between vast­ly dif­fer­ent lan­guages. So it was with the the­o­ret­i­cal devel­op­ment of Indo-Euro­pean as a lan­guage fam­i­ly, a slow process that took sev­er­al cen­turies to coa­lesce into the mod­ern lin­guis­tic tree we now know."

Reconstruction of lost sources can be controversial and requires inference from textual traces such as diction, syntax, stylistic, and thematic signatures. Many ancient Hebrew and Christian biblical passages preserve remnants of earlier texts that exist in no physical form and must be inferred from those traces. Oral cultures long predate writing, so tracing linguistic ancestors can reach the origins of human culture and depends on sparse archaeological evidence and audible similarities between distant languages. The Indo-European family emerged gradually over centuries into a coherent linguistic tree. Early observers noted Sanskrit’s resemblance to Greek and Latin, with later nineteenth-century advances.

Read at Open Culture

Unable to calculate read time

Collection

[

|

...

]