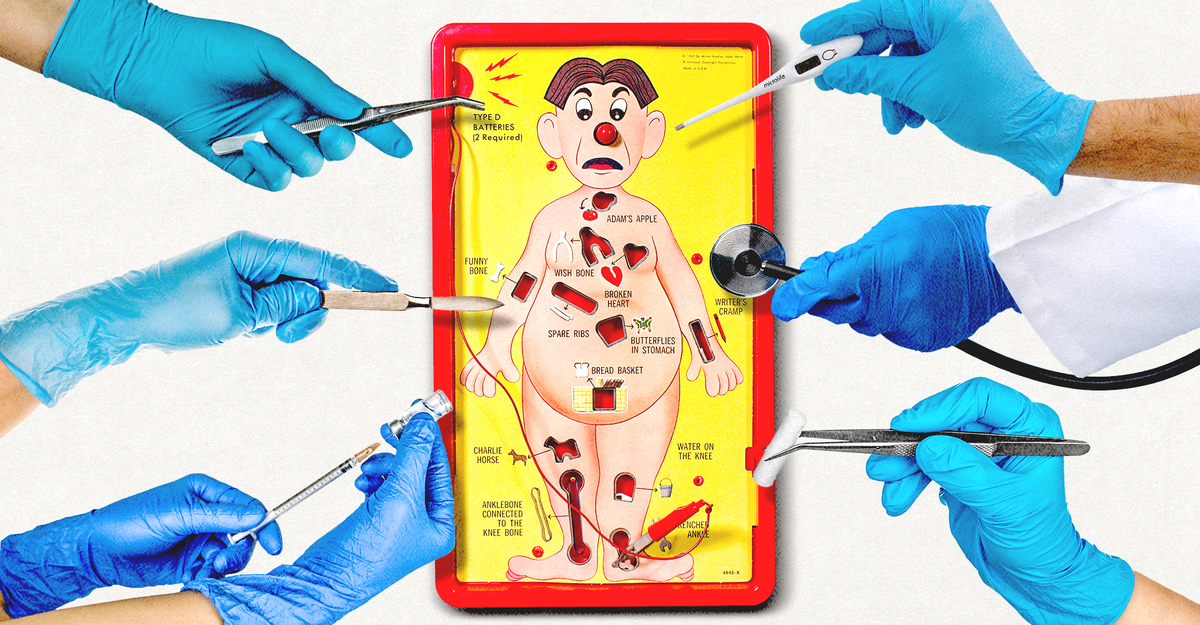

"Every few weeks I turn up in a hospital gown at a medical exam room in Massachusetts and describe a set of symptoms that I don't really have. Students listen to my complaints of stomach pain, a bad cough, severe fatigue, rectal bleeding, shortness of breath, a bum knee, HIV infection, even stab wounds; on one occasion I simply shouted incoherently for several minutes, as if I'd had a stroke. Then the students do their best to help."

"I have been given nearly 100 ultrasounds in just the past year, and referred to behavioral counseling dozens of times. I have been consoled for my woes, thanked for my forthrightness, congratulated for my efforts to improve my diet. I have received apologies when they need to lower my gown, press on my abdomen, or touch me with a cold stethoscope."

A volunteer portrays a wide range of illnesses repeatedly so medical students can practice clinical encounters and diagnostic reasoning. Students hear complaints including stomach pain, cough, fatigue, rectal bleeding, shortness of breath, joint injury, HIV infection, and simulated stroke symptoms, then examine, test, counsel, and deliver diagnoses. Encounters can include ultrasounds, behavioral-counseling referrals, apologies for intimate exams, and unhurried discussions of tests, treatments, and medications, sometimes lasting up to 40 minutes. Training for standardized patients involves multiple days of instruction and study. The method originated in 1963, with a University of Massachusetts program formalized in 1982 and later becoming widely adopted.

Read at The Atlantic

Unable to calculate read time

Collection

[

|

...

]