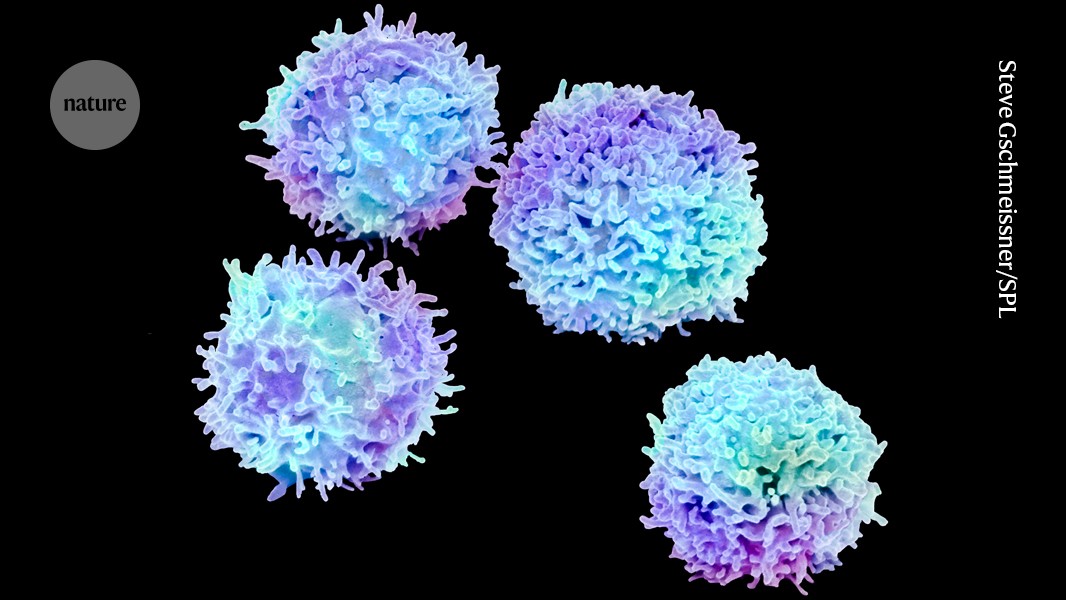

"The class of immune cells at the centre of Monday's Nobel prize is showing promise as a treatment for autoimmune diseases, cancer and even organ transplants - but there are still key challenges to overcome before these cells can be used in therapies in the clinic. Regulatory T cells, or T reg cells, help to prevent the body from attacking its own tissues."

"Thirty years after Sakaguchi and his colleagues reported the discovery of T reg cells, there are more than 200 clinical trials of the cells under way, for conditions such as type 1 diabetes, motor neuron disease and a host of autoimmune diseases - including multiple sclerosis, lupus and a group of rare skin disorders called pemphigus. The cells are also being tested for their ability to keep the immune system from rejecting transplanted tissues."

""There's a lot of excitement about recruiting regulatory T cell activity to treat a range of autoimmune or inflammatory disorders, but also in the context of tissue and cell transplants," says Daniel Gray, a T reg-cell researcher at the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research in Parkville, Australia. But the rarity and fragility of these cells pose difficulties to their widespread application, researchers say."

Regulatory T cells (T reg cells) prevent the immune system from attacking the body's own tissues and are being pursued as therapies for autoimmune diseases, cancers and transplant rejection. Three scientists credited with discovering and characterizing these cells spurred research that led to more than 200 clinical trials targeting conditions such as type 1 diabetes, motor neuron disease, multiple sclerosis, lupus and pemphigus. Researchers are excited about harnessing T reg-cell activity for inflammatory and transplant contexts. Practical hurdles include the cells' rarity and fragility, which complicate manufacturing, delivery and sustained function in patients.

Read at Nature

Unable to calculate read time

Collection

[

|

...

]