"Smyth thinks that so few adults show up on the fossil record in this region not only because they were more likely to survive, but also because those that couldn't were not buried as quickly. Carcasses would float on the water anywhere from days to weeks. As they decomposed, parts would fall to the lagoon bottom. Juveniles were small enough to be swept under and buried quickly by sediments that would preserve them."

"The humerus fractures found in Lucky I and Lucky II were especially significant because forelimb injuries are the most common among existing flying vertebrates. The humerus attaches the wing to the body and bears most flight stress, which makes it more prone to trauma. Most humerus fractures happen in flight as opposed to being the result of a sudden impact with a tree or cliff. And these fractures were the only skeletal trauma seen in any of the juvenile pterosaur specimens from Solnhofen."

"Evidence suggesting the injuries to the two fledgling pterosaurs happened before death includes the displacement of bones while they were still in flight (something recognizable from storm deaths of extant birds and bats) and the smooth edges of the break, which happens in life, as opposed to the jagged edges of postmortem breaks. There were also no visible signs of healing."

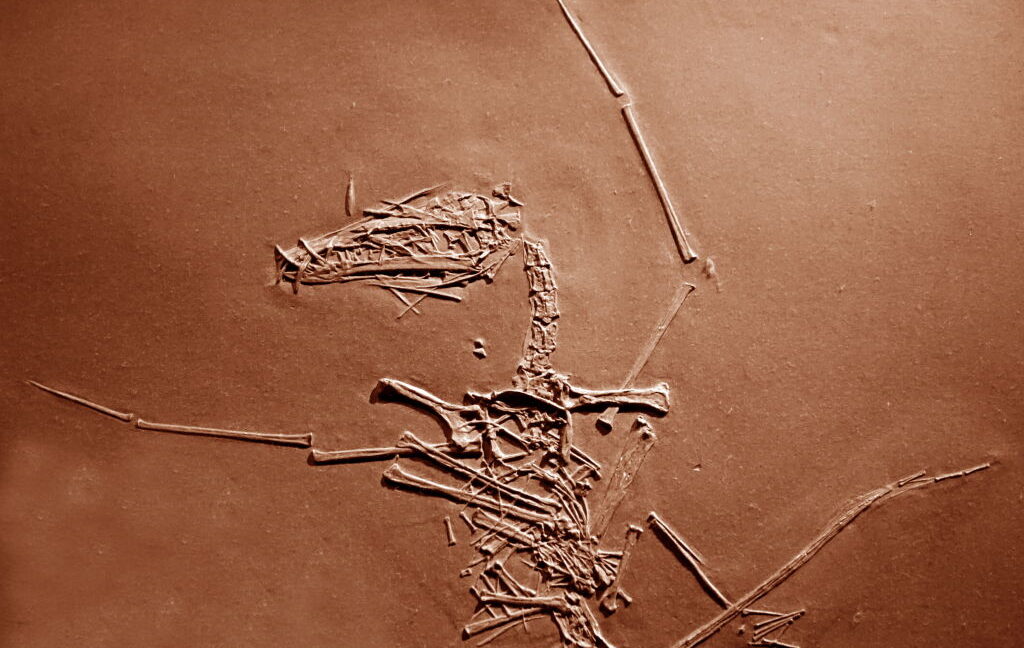

Few adult pterosaur remains occur because adults often escaped rapid burial; carcasses floated for days to weeks and decomposed, with parts falling to the lagoon bottom. Juveniles were small enough to be swept under sediments and buried quickly, leading to their preservation. Two juvenile specimens show humerus fractures, the forelimb bone that bears most flight stress and commonly breaks in flight. The fractures display displacement and smooth break edges, indicating perimortem injury with no signs of healing. Intense storms frequently downed flying animals and churned lagoons, bringing high-salinity, low-oxygen deep water that inhibited scavengers and promoted exceptional fossil preservation.

Read at Ars Technica

Unable to calculate read time

Collection

[

|

...

]