Artificial intelligence

fromTechCrunch

1 week agoChina's brain-computer interface industry is racing ahead | TechCrunch

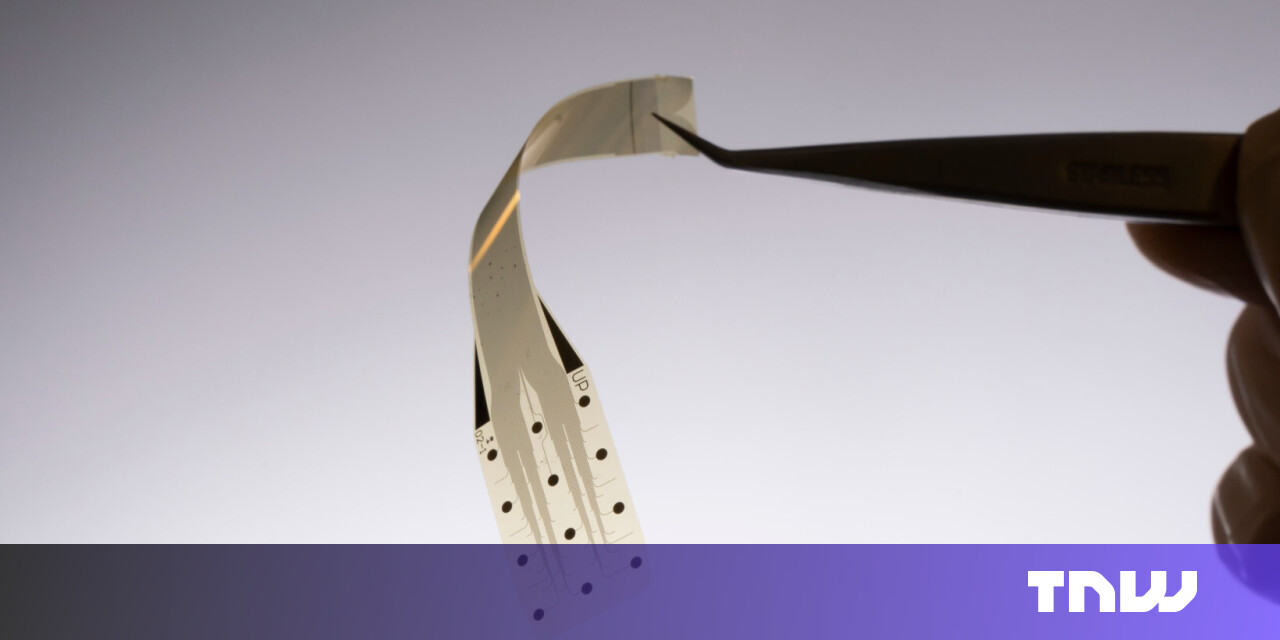

China's BCI industry is shifting from research to commercial scale, with startups, policy support, clinical trials, and insurance expansion driving multibillion-dollar healthcare growth.