fromMail Online

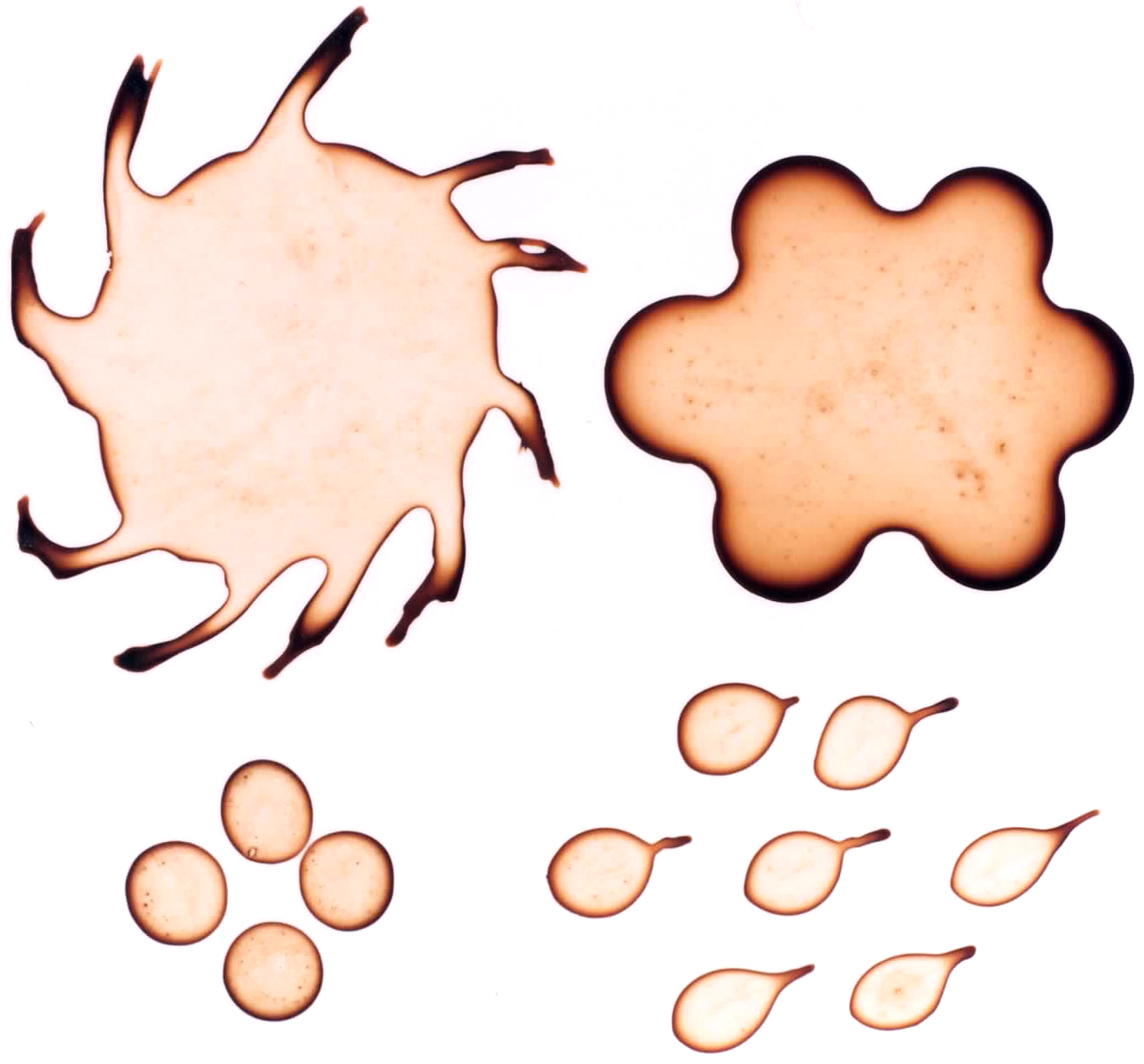

2 weeks agoScientists reveal secret behind the perfect pancake toss

'To get it to flip, linear force isn't enough,' one of their researchers said. 'We need a pivot point. 'For the pancake to flip, it must rotate. This comes from torque, which happens when the pan pushing slightly off the pancake's centre of mass, giving it angular acceleration.'

Science