#consciousness

#consciousness

[ follow ]

#neuroscience #artificial-intelligence #philosophy #philosophy-of-mind #panpsychism #psychology #perception

fromBig Think

4 days agoThe hard problem of consciousness, in 53 minutes

My work focuses on what makes consciousness such a deeply perplexing phenomenon and a mysterious phenomenon, why it's so difficult for scientists to study it, and because it's such a mysterious phenomenon still within neuroscience, part of my work has also been to connect different disciplines that aren't usually in dialogue. With consciousness studies, if we're interested in asking the question about whether consciousness goes deeper in nature than the sciences have previously assumed, we start to come out of neuroscience

philosophy

fromPsychology Today

2 weeks agoThere Goes the Sun: Pondering the Universe's Past and Future

A key goal, writes the author, Bobby Azarian,is to argue against the view that life is an unlikely accident that may have emerged only once on one tiny speck in a vast universe, and that it is certain to disappear as the universe's free energy dissipates in accordance with the second law of thermodynamics. He argues that while such a conclusion had for several generations seemed to be the destination to which clear-headed scientific exploration had brought mankind,

Science

fromPsychology Today

1 month agoThe Hidden Connection Between Information and Consciousness

The ordered state is a low-entropy state, and entropy measures the system's proximity to the most probable (equilibrium) state. Therefore, a system is "far from equilibrium" if its components are statistically correlated, because correlation among components is order. When parts are correlated rather than independent, you have structure.The system occupies a state that's improbable relative to chance. You can predict something about one part by knowing about another.

Science

fromPsychology Today

1 month agoAn Introspective Test of Global Workspace Theory

Global Workspace Theory is among the most influential scientific theories of consciousness. Its central claim is: You consciously experience something if and only if it's being broadly broadcast in a "global workspace" so that many parts of your mind can access it at once - speech, deliberate action, explicit reasoning, memory formation, and so on. Because the workspace has very limited capacity, only a few things can occupy it at any one moment.

philosophy

fromMail Online

1 month agoRadical new theory of consciousness explains what happens when you die

Consciousness does not emerge from human brains, according to Professor Maria Strømme, a professor of nanotechnology at Uppsala University. Instead, she claims that it exists as a fundamental field. If this is correct, 'mysterious' phenomena such as telepathy, near-death experiences, and even life after death could finally be explained by science. According to Professor Strømme's theory, consciousness does not end when we die. Instead, when a person passes away, their consciousness simply returns to the background field.

Science

fromColossal

2 months agoMichael Velliquette's Metallic Paper Sculptures Delve into the Nature of Consciousness

The Light That Sees, Velliquette's solo exhibition of 21 new works at Duane Reed Gallery, delves into themes of consciousness and light, both in the physical sense that light enables us to see but also in the way that illumination is itself a metaphor for awareness-and enlightenment. Through monochromatic reliefs, he highlights perception, material, and the human relationship with nature.

Arts

fromInsideHook

3 months agoTreatment for Epilepsy Expands Understanding of Sleep

The more scientists research how we sleep, the more they discover how important sleeping is to our overall health and wellbeing. But those aren't the only sleep-related discoveries scientists are making. The latest high-profile finding is less about the benefits of sleep and more connected to how the brain behaves during sleep, something that could have wider implications for our understanding of the human body.

Medicine

fromNature

3 months agoDisconnecting part of the brain sends it into a deep sleep

The team wanted to find out whether the disconnected part has some form of awareness - or was capable of exhibiting consciousness, says co-author Marcello Massimini, a neurophysiology researcher at the University of Milan in Italy. "The question arises because we have no access" to the disconnected region, he says, adding that it was unclear what happens once part of the brain is isolated.

Medicine

fromBig Think

3 months agoYes, reductionism can explain everything in the whole Universe

There's a statement that one can make that would have been completely non-controversial at the end of the 19th century, but many people both in and out of science would argue against it today. Consider for yourself how you feel about it: "The fundamental laws that govern the smallest constituents of matter and energy, when applied to the Universe over long enough cosmic timescales, can explain everything that will ever emerge."

philosophy

philosophy

fromThe Beer Thrillers - Central PA beer enthusiasts and beer bloggers. Homebrewers, brewery workers, and all around beer lovers.

3 months agoThe Meaning of Life - as per ChatGPT and Perplexity - The Beer Thrillers

Life's meaning emerges from existence, awareness, and connection, where conscious experience, self-reflection, and relationships create purpose and value.

fromPsychology Today

3 months ago'The Secret of Secrets': Is the Science Accurate?

Dan Brown's latest thriller, The Secret of Secrets, follows neuroscientist Katherine Solomon as she reports how low GABA, an inhibitory neurotransmitter in the nervous system, expands consciousness. She states in her research that low levels of GABA enable things like telepathy, remote viewing, and more. She explains that on our deathbeds, we experience a precipitous drop in GABA, revealing to us what lies beyond. Her science leads to a mind-bending cat-and-mouse chase around the most beautiful parts of Prague.

Science

fromPsychology Today

3 months agoA Look Behind the Camera Into the Productions of Our Minds

"The man (person) behind the camera" refers to an observer or witness not only to the surrounding world, but also to one's own sensations, feelings, impulses, instincts, thoughts, and experiences. Seeing more than their external and internal environments, this observer has a higher level of awareness, the cognitive awareness of awareness, or meta-awareness. Within the animal world, humans have been described as uniquely being aware of being aware.

philosophy

fromWashingtonian - The website that Washington lives by.

4 months agoWhat Happens After We Die? UVA Researchers Are Investigating It.

It's mind-bending, norm-challenging work that explores the metaphysical-which is why I'd expected something a little more mystical. A spiral staircase, an owl, a crystal ball. The divination tower at Hogwarts. Certainly not a mid-rise straight out of Anywhere, USA. Only there it was, visible through the glass front door: a placard in the lobby reading "Division of Perceptual Studies." The door handle turned with a wiggle.

Science

fromPsychology Today

4 months agoPsychology Returns to the Nature of the Mind

In his Introduction to Psychology, the father of psychology as a scientific discipline, Wihlem Wundt, wrote that "This science has to investigate the facts of consciousness, its combinations and relations, so that it may ultimately discover the laws which govern these relations and combinations." However, his use of introspection, or "internal perception," lacked the tools for observing, reproducing, or experimentally modulating these internal perceptions, and the field of psychology was on the brink of collapse.

philosophy

fromPsychology Today

4 months agoThe Subliminal Mind and the Superconscious

Unlike many modern psychologists, he felt the field should encompass paranormal phenomena and mystical experiences. As well as writing one of the great studies of mystical experiences, The Varieties of Religious Experience, he self-experimented with psychoactive substances such as nitrous oxide and ether. (From this perspective, a mystical experience is an experience of heightened awareness, in which the world becomes more vivid and beautiful, and there is a sense of oneness and bliss, as well as a sense of meaning and revelation.)

Psychology

fromwww.theguardian.com

4 months agoThe Secret of Secrets by Dan Brown review weapons-grade nonsense from beginning to end

Do we learn more about Langdon? Not much. He is still so world-renowned that, as doesn't happen for most academics, fancy hotels monogram his slippers for him. His password for most things is Dolphin123, because he's good at swimming. He is too old-fashioned to like texting or videogames, and just a little prudish. He has never seen When Harry Met Sally, but has heard about the famous sex scene'.

Arts

fromwww.scientificamerican.com

4 months agoIs Consciousness the Hallmark of Life?

More than half a billion people around the world have downloaded artificial-intelligence chatbot companion apps such as Xiaoice and Replika. These virtual confidantes can provide empathy, support and, sometimes, deep relationships. Chatbots, of course, aren't consciousthey just feel that way to users, who often become emotionally attached to them. As AI grows more fluent in mimicking human empathy, language and memory, we're left to confront an uneasy problem: If a machine can fake awareness so well, what exactly is the real thing?

Artificial intelligence

fromThe Conversation

4 months agoCan you be aware of nothing? The rare sleep experience scientists are trying to understand

For some people, sleep brings a peculiar kind of wakefulness. Not a dream, but a quiet awareness with no content. This lesser-known state of consciousness may hold clues to one of science's biggest mysteries: what it means to be conscious. The state of conscious sleep has been widely described for centuries by different Eastern contemplative traditions. For instance, the Indian philosophical school of the Advaita Vedanta, grounded in the interpretation of the Vedas - one of the oldest texts in Hinduism - understands deep sleep or "sushupti" as a state of "just awareness" in which we merely remain conscious.

philosophy

fromBig Think

4 months agoSam Harris: Experience emotions without being consumed by them

I mean, the amazing thing about our circumstances that each one of us is in a position that is in some sense, as free and as profound and as in touch with reality, as any other position in this universe, where you stand, the universe is illuminated as you, as your experience in this moment. And that we call this substratum of experience, consciousness, for lack of a better word.

Mindfulness

#memory

Mindfulness

fromPsychology Today

7 months agoWhat Remains When Memory Fades

Memory loss does not erase the self; love and imagination remain.

Psychedelics suggest consciousness can exist without autobiographical memory.

Identity consists of relational patterns, not solely stored memories.

Connection preserves dignity, emphasizing the importance of presence.

fromBig Think

5 months agoHow the illusion of self shapes your reality

The sense that we are a solid entity, an unchanging entity that exists someplace in our body and takes ownership of our body, and even ownership of our brain rather than being identical to our brain, that is where the illusion lies.

philosophy

fromAeon

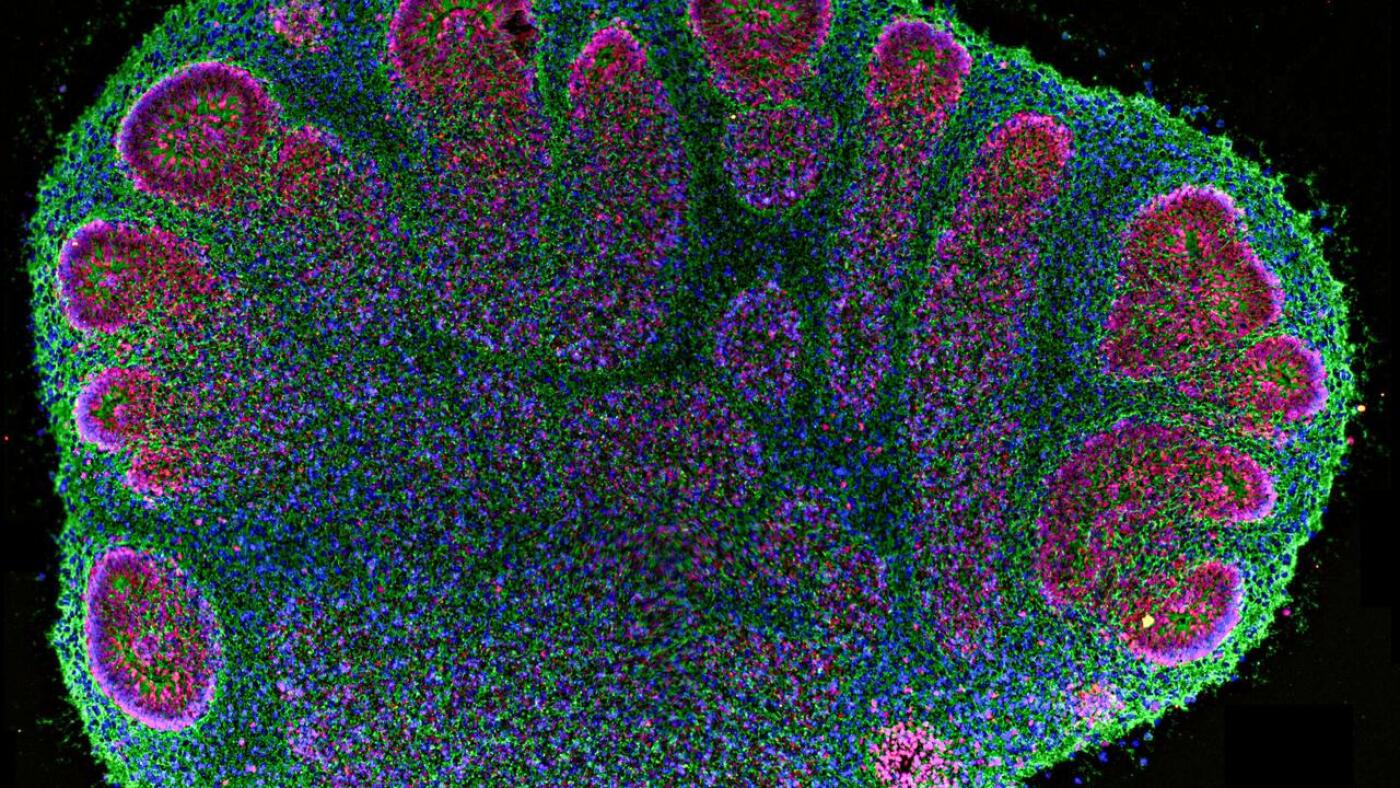

6 months agoHow jazz and dolphins can help explain consciousness | Aeon Essays

Increasingly, organoids are being fused to create 'assembloids', complexes of interacting organoids. Sergiu Pasca's laboratory at Stanford University has created an assembloid that models the human spinothalamic pathway, a neural circuit critical for the transmission of sensory information from the body to the brain.

philosophy

fromHarvard Gazette

6 months agoMeditation provides calming solace - except when it doesn't - Harvard Gazette

Matthew Sacchet, director of the meditation research program at Harvard Medical School, indicates that meditation, while beneficial for many, can also lead to significant suffering in some individuals. This unexpected outcome has prompted calls for greater scrutiny by researchers and clinicians into the effects of meditation beyond its therapeutic applications.

Mental health

[ Load more ]