Women

fromFortune

10 hours agoWhy women's earnings plateau in their 30s while men's just keep growing through their 40s: It's not just motherhood | Fortune

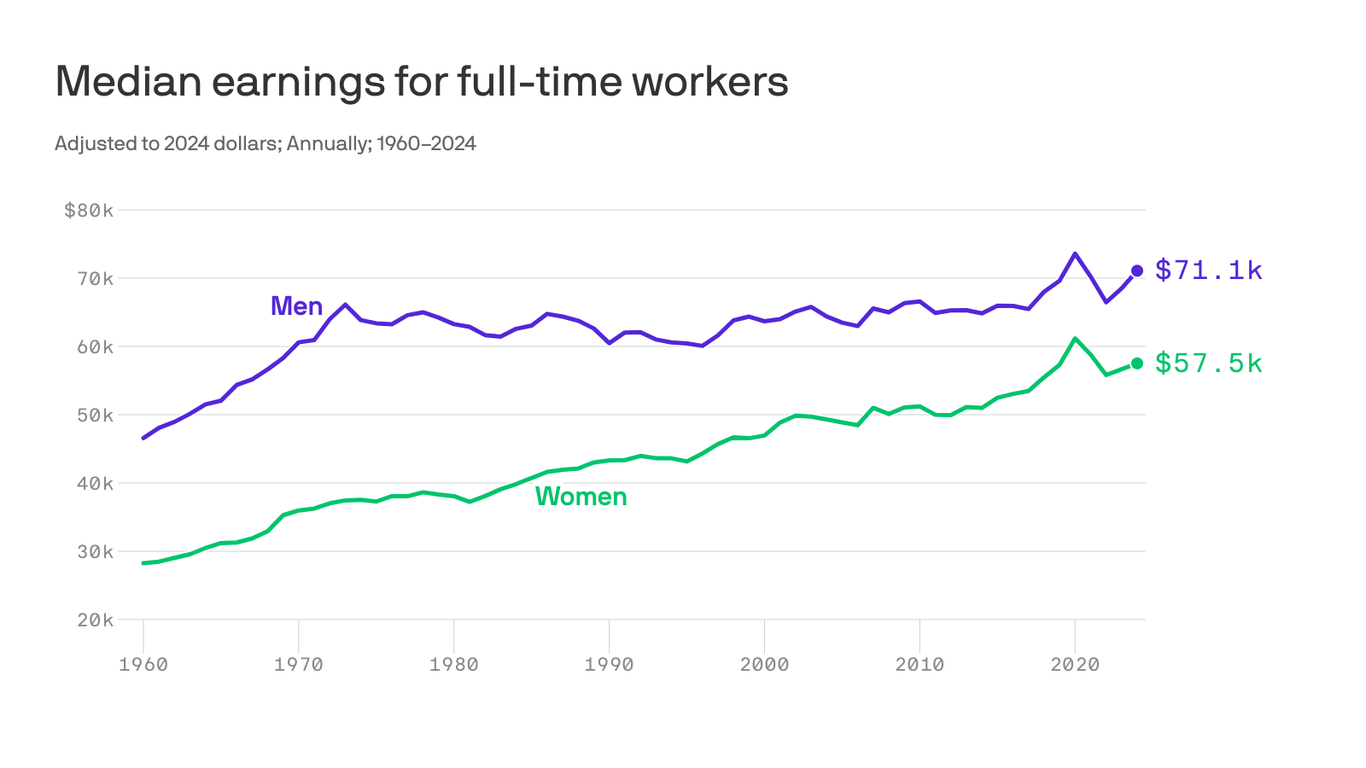

Women's wages plateau in their late 30s while men's earnings continue climbing, creating a 25% gender pay gap by 30 years of experience, driven primarily by men advancing into higher-paying roles at faster rates.