#evolution

#evolution

[ follow ]

#paleontology #scopes-trial #genetics #technology #natural-selection #biodiversity #astrobiology #fossils #biology

fromPsychology Today

1 month agoWhat the Heart Remembers: Photo Collectors

Olivia, our granddaughter, said, " If there isn't a photo, it didn't happen." This may be a bit extreme, but to some, photography freezes time with an immediacy no other medium can match. A photo is an imprint of something that truly exists: a person, a place, or a gesture. To accumulate such images is to collect moments that survive.

Photography

fromBig Think

2 months agoWhy desire - not resilience - leads to longevity

"We've glorified resilience as this virtue," he told me. "Bounce back, return to normal, weather the storm. But the literal definition of resilience is the ability of a system to return to its original baseline after being disturbed."

Venture

fromenglish.elpais.com

3 months agoFossils found in Kenya shed light on the origin of human hands

For a long time, Paranthropus boisei, a hominid that inhabited the Earth from 2.6 million years ago to 1.3 million years ago, had been considered by experts to be a relative of humans. Its robust jaw, large molars, and powerful chewing muscles evidenced a diet as primitive as it was difficult to process, consisting of tough grasses and reeds that other species perhaps couldn't consume.

Science

fromPsychology Today

3 months agoWhere Do Cognition and Consciousness Begin?

The systemic set of processes that enables value-sensitive acquisition, encoding, evaluation, storage, retrieval, decoding and transmission of information. All learning systems are cognitive systems. All living systems and artificial learning-systems are therefore cognitive systems. In other words, cognition is the capacity to learn from experience in a value-sensitive way-discriminating what is beneficial or harmful, and with behavior shaped accordingly.

Science

fromMail Online

4 months agoIf evolution is real, why are there still monkeys?

When you learned about the history of human evolution in school, there's a good chance you were shown one all-too-familiar image. That picture probably showed a conga line of human-like creatures, from a primitive ape at one end to a modern man proudly strolling into the future at the other. For many people, this iconic image captures evolution's slow but inevitable march from the simple to the complex.

Science

fromwww.scientificamerican.com

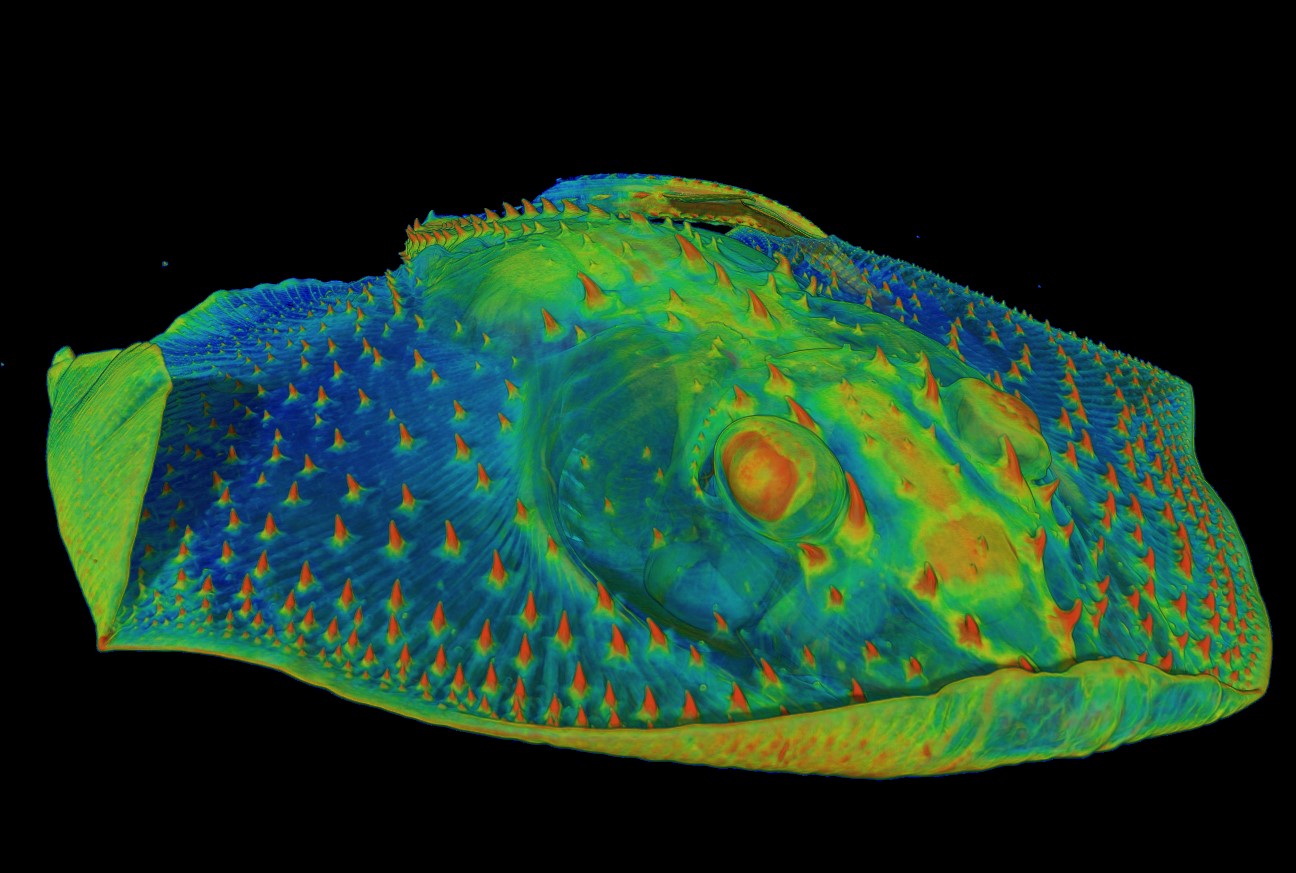

4 months agoBehold the Gloriously Weird Spotted Ratfish. It Has Teeth on Its Forehead for Sex

The spotted ratfish is a two-foot-long fish with a big head and a long, skinny tail that lives in the northeastern Pacific Ocean. It belongs to a group of fish called chimaeras that are closely related to sharks. (Chimaeras are sometimes called ghost sharks.) Like most vertebrate creatures, it has teeth in its mouth. Unlike other vertebrates it also has teeth in another location: its forehead. It uses these forehead teeth for sex.

Science

fromBig Think

4 months agoThe history of natural selection, in 7 minutes

Charles Darwin's theory of natural selection did more than explain evolution, it revealed how complexity can emerge without a designer. Nobel laureate Paul Nurse unpacks Darwin's insights, from the logic of tiny differences to the profound impacts these variations have on our understanding of life. Nurse explores the deep genetic connections linking all organisms, from humans to gorillas to yeast. This shared ancestry, he argues, reframes how we think about responsibility: If all life is related, what do we owe to the living world?

Science

fromwww.theguardian.com

4 months agoEverything Evolves by Mark Vellend review can Darwin explain JD Vance?

Nobody expected the Spanish Inquisition, but then again no one could have predicted the giraffe, the iPhone or JD Vance. The laws of physics don't demand them; they all just evolved, expressions of how (for better or worse) things happened to turn out. Ecologist Mark Vellend's thesis is that to understand the world, physics and evolution are the only two things you need. Evolution, here, refers in the most general sense to outcomes that depend on what has gone before.

Science

Science

fromwww.nature.com

6 months agoMeet the Solar-Powered Slug That Steals Photosynthetic Machinery from Algae for Emergency Food

Sea slugs possess specialized compartments that store and maintain functional chloroplasts, allowing them to photosynthesize.

The slugs can consume stored chloroplasts for energy in times of scarcity.

Science

fromwww.independent.co.uk

6 months agoGarden slugs and snails could now be considered venomous, study finds

Many species previously deemed harmless may be recognized as venomous, altering our understanding of venom.

New definitions of venom could expand classifications significantly in evolutionary research.

Mindfulness

fromPsychology Today

7 months agoWhy Don't We All Think the Same?

Cognitive diversity is crucial for group survival by providing different perspectives.

Differences in perception arise from biology, emotion, and personal experiences.

Unique viewpoints help groups adjust to changing environments.

Marketing tech

fromVerticalResponse

7 months agoInbox Nostalgia: What Marketing Emails Looked Like in 2005 vs Today

Email marketing has evolved from text-heavy formats in 2005 to today's personalized and visually rich designs.

The transformation is influenced by technology, consumer behavior, and regulations.

Modern best practices focus on engaging content, data optimization, and regulatory compliance.

Today's email marketing enhances engagement, targeting, and ROI for businesses.

Parenting

fromPsychology Today

7 months agoWhat Can We Learn From Chimpanzees?

Chimpanzee development mirrors human learning and socialization intricately.

Young chimps have superior visual memory compared to humans.

Chimpanzees display culture and compassion, challenging perceptions of animal intelligence.

fromwww.theguardian.com

7 months agoArctic, feathered or just weird: what have we learned since Walking with Dinosaurs aired 25 years ago

The public wasn't ready for it... Now we're at the point where we've got dozens of species definitively feathered and probably over a hundred where we're very confident they had feathers.

OMG science

[ Load more ]